A Rant on Indifference to Christian Discrimination in the Middle East

By Yousif Kalian

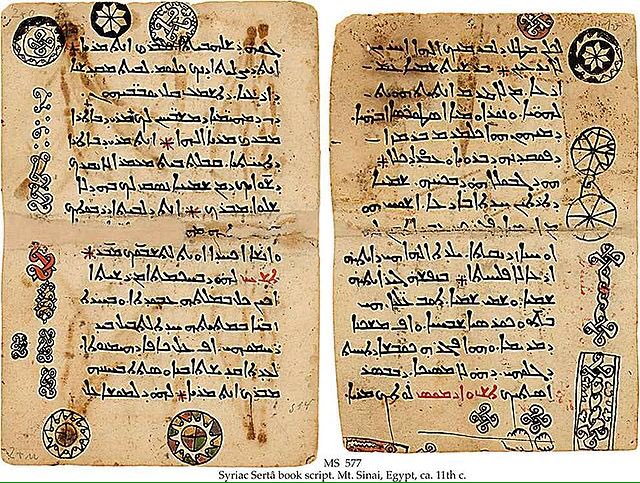

St. Catherines Monastery, Mt. Sinai, Egypt. Courtesy of Wikicommons.

Don’t treat Christian privilege in the region as you would in the West.

THIS recent Easter weekend, across the Arab world, Christians gathered to celebrate the crucifixion, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. The parishioners of these churches are descendent of the ancient Babylonians, Egyptians, Assyrians and Phoenicians.

For hundreds and even thousands of years, we have prided ourselves on being bearers of culture and connecting the knowledge of the east with the knowledge of the west, and vice-versa. Christians are incredibly proud of their own cultural heritage: arts, literature, and music, and especially love sharing our heritage with our non-Christian neighbors.

But, this past Easter weekend, Christians gathered both in fear and in hope, finding comfort in equivocating their suffering with that of Jesus’. They carried burdens that weighed heavily on their shoulders, the same way Jesus carried the literal burden of his cross.

It was recently stated in the movie Silence that “the seed of the church is the blood of martyrs.” For Christians of the Middle East, this statement is powerful for the truth it speaks to their current situation. The events of this past Holy Week have done nothing but reinforce this sad truth in blood.

Following a devastating Christmas attack on a chapel adjacent to Egypt's main Coptic Christian cathedral in Cairo which left 30 people dead, twin Palm Sunday bombings hit churches in Alexandria and Tanta, leaving 43 dead and terrifying the community to its core as the attackers narrowly missed a ceremony presided over by Coptic Pope Tawadros II. Egyptian TV repeated what President El-Sisi's oft-repeated script: "These victims were not Muslim or Christian; they were Egyptian!” which, in effect, is the Egyptian nationalist version of “All Lives Matter.”

Even in light of this hyper-nationalism surrounding the Palm Sunday attacks, churches in Minya were targeted by their neighbors throwing rocks at them. In an interview with Wael El-Ibrashy, the nephew of a police officer killed in the Alexandria Church bombing said the police officer was uncomfortable at being chosen to secure the church. She allegedly asked her nephew “if I am killed (defending the church) will I be considered a martyr?” All of this is coupled with the recent ethnic cleansing taking place in the northern Sinai city of Arish, where hundreds of Christians have fled after the Islamic State (ISIS) killed several Copts and called for a purge of all Christians from Egypt.

However, when discussing the roots of Christian persecution and emigration, it is dangerously easy to demonize Islam and Muslims. As a matter of fact, Christians and Muslims have lived together in mutual concord and respect for many centuries. In Iraq, Christians started leaving in the 1990s because of economic sanctions, not persecution. In Shiite neighborhoods, most notably in Dahiya in Lebanon and Najaf in Iraq, pictures of the Virgin Mary are found scattered next to images of Ali. When my mother's hometown of Mosul was overtaken by ISIS and expelled Christians, her Muslim friends called her crying apologizing for what has been done in the name of their religion even though they were not involved whatsoever. This past Holy Week in Jordan saw dozens of Muslim youth standing as guards in front of churches to ensure the safety of Christians inside, in response to the attacks in Egypt.

But persecution doesn’t occur in a vacuum. In Egypt, phrases like “Masihee bes kways” ([They’re] Christian, but [they’re] alright) are widespread, addressing a supposed abnormality of Christians being 'good' people. The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood regularly makes offensive and hateful statements regarding Christians, going so far as to blame the Coptic people for being involved in a conspiracy to use the targeting of churches as a way to empower Sisi’s police state.

These conspiracies and statements purported by the Brotherhood aren’t limited to random youth either; just the other day a leader of the Muslim Brotherhood’s political party Gemal Heshmet claimed that “those who rule the world (Jewish & Christian religious extremists)” were involved in a conspiracy preventing Islamists from governing stably. With this being the case, does it really come as a shock that ISIS’s statement claiming the Palm Sunday attacks spoke of Egyptian Christians as ‘crusaders,’ despite the Coptic community predating any conflict between Europeans and Muslims?

Less than two weeks after the Palm Sunday church attacks, ISIS launched an attack on a police checkpoint near the entrance to St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt's south Sinai, killing 1 policeman and injuring 4 others. This attack is particularly frustrating since St. Catherine’s Monastery holds a special place in Islamic and Christian history. According to tradition, the Muslim prophet Mohammed both knew and visited the monastery and its Sinai priests, and mentions of the holy site are found throughout the Quran. In 623 A.D., the priests of the monastery requested a letter of protection from Mohammed, which he duly granted and authorized by placing his hand on the document. As the website of the monastery puts it:

“The continuous existence of the monastery during fourteen centuries of Islamic rule is a sign of the respect given to this Letter of Protection, and the principles of peace and cooperation that it enshrines.”

Too often do Muslims fall into the belief that Christianity is a foreign entity in their lands implanted by Europe or that they were somehow corrupted and made worse by European colonization. In Iraqi schools, even under the supposedly secular Ba'ath party, the history of Christians is never discussed. This erasure feeds into the belief that Christians are an outside European colonial implant and not native sons of the land – a belief held by many Europeans as well, who are usually shocked to learn that Christianity exists in the Middle East.

But Muslims are not the only ones who dismiss discrimination against Christians in the Middle East through an oversimplified narrative of 'otherness'. In the West, the plight of Christians of the Middle East is also often lost upon deaf ears. Indeed, as many have put it, Middle Eastern Christians are too religious for the progressive left and too foreign for the conservative right. Western blindness to Middle Eastern Christians is related to the issues of Islamophobia and anti-Arab fears, in that many in the West are not willing to comprehend that the Arab and Muslim world contains significant levels of religious or ethnic diversity. Even when presented with information on Christian persecution in the Middle East, right wing pundits use the persecution to show why the Middle East is a bad place and why Muslims are bad people, while left wing pundits fail to understand the breadth of this persecution since it doesn’t fit their hierarchy of victimhood. During the first five years of the Iraq war, when the Christian population of Iraq declined from 1,500,000 to 400,000, the Bush administration cared little to their plight. It was not until the rise of ISIS did American conservatives start to care about the Christians of Iraq, or the Middle East as a whole.

Sadly, this has been the status quo for a long time. With similar dynamics happening across the Arab world, it is no mystery many are predicting the end of Christianity in the Middle East in a few decades. The future, although looking dark, does have small glimmers of hope -- even in Iraq, where the Christian population was 1,500,000 before 2003 and dropped to a little under 250,000 in 2014.

Christians trickled back into their villages and towns of the Nineveh Plains to celebrate the Holy Week after suffering genocide at the hands of ISIS and fleeing to the relative safety of Kurdistan. Since many Christians are still scarred by their neighbors turning on them, their probability of return is low. But, in interview after interview with leaders and commoners of the Christian community, many insist that they will return. Meanwhile, in the diaspora churches, Middle Eastern Christians have served as a bridge between East and West for many in their new countries by bringing Middle Eastern food and culture with them.

Discussion of Christians across the Levant and Iraq has shifted to be more compassionate to their suffering, which is a sure fire way to combat deeply held negative views of Christians in the region. For example, the victory of Arab Idol singer Yacoub Shaheen, a Syriac Christian, and Palestinian, shows the strength of the desire of coexistence. Winning the most popular season of the competition with a picture of a church being shown behind him reflects the willingness of so many to stand in solidarity with their persecuted neighbors.

Having hope for the future of Christian existence in the region isn't an impossible task, despite the looming darkness and difficulties. Even if it is inevitable, and the diaspora communities are the future of Middle Eastern Christianity, forgetting that Christians are native inhabitants of the Arab world and not just "remnants of European colonialism" insults the heritage of the Arab world. The lack of outrage throughout the world is a signal of the ironic intolerance and complacent indifference towards the situation of Christians in majority-Muslim countries.

In an Easter message, the Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic church in Iraq, the largest Christian denomination in Iraq and one of the largest across the Middle East, called for Christians to:

“Deepen their fidelity to Christianity and to their Church; strengthen their affiliation to their homeland; renew trust and consolidate ties with their fellow citizens of different backgrounds; and to keep in mind that their presence in this land is a sign and a story of a historical existence for 20 Centuries.”

He also called upon his flock to work efficiently with their fellow Iraqi citizens of different faiths, to confront challenges they face together as a nation in order to guide Iraq by promoting diversity and respect within the framework of a full citizenship. The Patriarch’s statement reflects the strong will of many Christians of different denominations to stay in their homeland and help rebuild it after the chaos brought on by the Arab Spring. For many, the death and resurrection of Jesus fills them with hope in the face of seemingly insurmountable issues. Understanding the difficulties Christians face without belittling the plight of their Muslim brothers and sisters is possible. Acknowledging persecution, spreading awareness and engaging in interreligious dialogue combats the deep rooted causes of persecution. Being an ally to this community helps preserve the beautiful mosaic that is the Middle East.