Namedropping

by Samuel Tafreshi

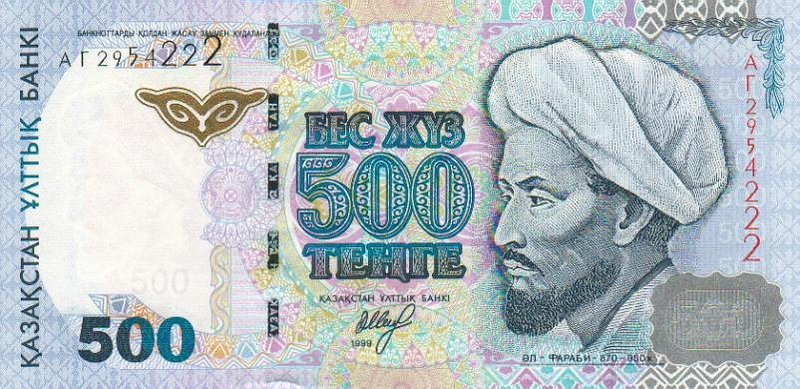

Khazakstani tenge bills (200, 2000). Images courtesy of author.

When examining a one tenge banknote, the currency of Kazakhstan, one will find the renowned intellectual al-Farabi staring back. While walking the streets of Tehran, it would not be surprising to encounter Ferdowsi Street, Ferdowsi Metro Station, or Ferdowsi Park along a route. Whether in statues or signs, speeches or stamps, references to influential figures from the Islamic Golden Age (786–1258 CE) permeate the modern states of the Middle East and Central Asia.

A variety of scholars have become icons of countries formed centuries after their deaths. Farabi, Ferdowsi, Ibn Sina, al-Biruni, and countless others’ images were adopted for the purpose of state-building during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The impressive legacy of these thinkers’ achievements granted them, and any association with them, a historical legitimacy that the ruling elites of fledgling nations needed to project their authority backward through time. The contemporary representations, geographically disparate as they are, suggest the only shared connection between these writers is their time period and the depth of their contributions. On the contrary, they were quite closely connected within the intellectual community of the Khurasan region. Today, their images have been reproduced in far-flung cities and their achievements have been claimed by a dozen different states. In turn, what had been its own ‘center’ of intellectual and cultural production became an overlapping periphery beholden to the interests of emerging ‘centers’ in the region.

The historical province of Khurasan encompassed modern day Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, northeastern Iran, southeastern Turkmenistan, and significant portions of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. While it covered a vast geographic area, Khurasan shouldn’t be understood in terms of its frontiers. Instead, the region was a realm of cities—easily accessible to one another through trade routes and political relationships. It began as a province of the Sasanian Empire, but reached its highest level of prominence as one of the three regions administered by the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258 CE). Khurasan had been the cradle of the Abbasid Revolution and under the Abbasid Caliphate its major cities—Bukhara, Herat, Merv, Nishapur, Samarqand—grew to rival Baghdad and Damascus in size, distinction, and splendor. The city of Merv, in modern-day Turkmenistan, became of such great importance to the Abbasid Caliphate that Caliph al-Ma’mun briefly moved the capital from Baghdad to reside there. Far from what were the traditional heartlands of the Islamic empires in Arabia, Syria, and Iraq, Khurasan was a hub for many of the greatest thinkers of the Muslim world. Whether by way of poetry, theology, or science, traces of Khurasan’s influence can be found in almost every discipline.

The scientists, mathematicians, poets, and philosophers of Khurasan contributed immeasurably to the development of medicine, geology, geography, poetic forms, and religious and philosophical discourse. Rudaki (d. 941 CE), born in present-day Tajikistan, is considered by many to be the father of Persian poetry. Only remnants of Rudaki’s canon have survived, but through the existing fragments he has been venerated as one of the first poets of the New Persian language. The Persian language of pre-Islamic Iran disappeared as a literary tongue following the Arab conquest of Iran (654 CE), only to re-emerge as New Persian having adopted the Arabic script in the ninth century. Rudaki was one of the writers, as well as Ferdowsi, who heralded its return by experimenting with new poetic forms like the ruba’iyyah (Persian quatrain) and adapting Arabic poetic forms, such as the qasida (ode), for the Persian language.

Famously, while serving the Samanid Amir of Bukhara, Rudaki’s poetic skill was enlisted to persuade the Amir to return to Bukhara. The Samanid ruler would traditionally spend spring and summer travelling outside the capital, Bukhara, to enjoy the other cities of his domain, but on this occasion he had become so enamored with Herat (in modern-day Afghanistan) that he planned to stay indefinitely. Rudaki composed a poem for the Amir, in the hopes the poem might encourage him to return to Bukhara:

O Bukhara, be happy, live long:

The cheerful Amir is returning to you.

The Amir is the moon, Bukhara, the sky;

The moon is returning to the sky.

The Amir is a cypress, Bukhara, the garden;

The cypress is returning to the garden.

The Amir was so moved by the poem that he instantly became homesick for Bukhara and, without boots, mounted his horse and began riding back.

The influence of Farabi on the field of philosophy was as far-reaching and significant as Rudaki’s accomplishments in poetry. At a time when the western interest in Hellenic philosophy had waned, Farabi (d. 950 CE), born in present-day Kazakhstan, took up the mantle of the Greek philosophers and played a vital role in Islamic philosophy by comprehensively reading and producing commentaries on Aristotle’s works. Farabi’s commentaries on Aristotle would also become central to Western philosophers of Christianity in the thirteenth century, such as St. Thomas Aquinas, as the West attempted to revive their own exploration of Greek philosophy. Ibn Sina (d. 1037 CE), another monumental figure in the study of Hellenic thought, infamously struggled to comprehend Aristotle’s Metaphysics as a young man in Bukhara until stumbling upon Farabi’s commentary in a bookstall.

Ibn Sina, later in his life, became incredibly well-versed in Aristotelian philosophy and sciences, as can be gleaned from his correspondence with his younger contemporary Biruni:

“This letter is in response to the questions sent to him by Abu Rayhan al-Biruni from Khawarazm… You requested—may Allah prolong your safety—a clarification about matters some of which you consider worthy to be traced back to Aristotle, of which he spoke in his book, al-Sama’ wa’l ‘Alam, and some of which you have found to be problematic.” Ibn Sina

In the tenth/eleventh century CE, Ibn Sina and Biruni (d. 1050), two of the greatest figures of Islamic thought, began a correspondence critiquing the ideas and concepts of Aristotle’s chief cosmological text, On the Heavens. In a series of letters sent across modern day Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, they investigated a range of ideas from the weight of heaven to the existence of other worlds. This geographically disparate relationship was made possible through the intellectual community of Khurasan, which connected these two remarkably active minds.

Perhaps Ibn Sina’s most influential ideas were those expressed in his canon of five medical texts, al-Qanun fi al-Tibb, that described the symptoms of diabetes, instructions for surgical procedures, studies of contagious disease and how to prevent them, as well as numerous philosophical and therapeutic remedies. His Qanun became the most popular and authoritative medical text throughout Asia, Africa, and Europe; in Europe, dozens of Latin translations could be found as well as Arabic editions that had been printed in Rome. Biruni vigorously studied Ptolemy’s works and, like Ibn Sina, produced an indispensable work of science and mathematics by finding Ptolemy’s miscalculations of the earth’s longitude/latitude and accurately correcting them. Grasping the relationship between Farabi’s work and Ibn Sina’s, as well as Ibn Sina’s and Biruni’s, is crucial to understanding the unparalleled and frenzied activity that took place in Khurasan during the Islamic Golden Age. The interconnection between these scholars of Khurasan was crucial to the development of their ideas during the period, but these relationships are obscured by the contemporary tendency to divide their legacies between nations.

In the span of only a few centuries, Rudaki, Ferdowsi, Ibn Sina, Farabi, and Omar Khayyam all shared the same library within the fortress of Bukhara and heralded the rebirth of the Persian language. From Ferdowsi’s epic poem, the Shahnameh, to Imam Bukhari’s collection of hadiths, Sahih al-Bukhari, the scholars of Khurasan produced many of the preeminent Arabic and Persian works of the Islamic Golden Age. It is interesting to note that while many throughout the world know of Rumi and Ibn Sina, most have never heard of Khurasan and would be surprised to learn that these writers hail from Balkh, Afghanistan and Bukhara, Uzbekistan, respectively. Considering the impact of these writers’ works and their continued prominence today, one must wonder how Khurasan, as their cultural center, has been so easily ignored in the formation of national histories of the Middle East and Central Asia.

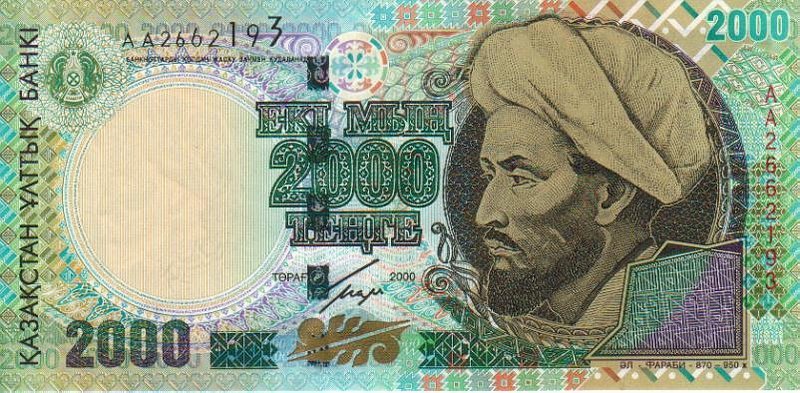

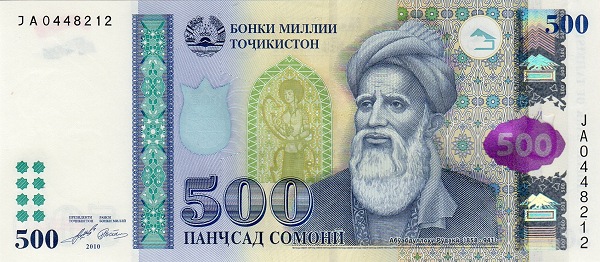

A history of military conquests, invasions, and occupations could explain Khurasan’s decline as a political and intellectual center, but it does not explain its absence in the national histories of contemporary states. How has Khurasan been so overlooked, while its iconic figures can be seen in the statues of Tehran and Vienna, on the banknotes of Tajikistan and Kazakhstan, and heard in the mouths of the most powerful contemporary leaders?

Khurasan’s vibrance diminished gradually, but it was not until the onset of Russian imperial domination in the latter half of the nineteenth century that the region’s past became fully obscured. The conquests and colonial occupations of the British and Russian Empires imposed new regional boundaries governed by imperial expansion. The further partitioning of Central Asia into five Soviet republics in 1924, under the USSR, attempted to erase previous connections and establish new political communities on an ethno-linguistic basis. The borders manufactured throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century gradually divided Khurasan between the states of Afghanistan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

Once, Merv could be reached as easily from Nishapur as from Herat or Bukhara; despite these cities’ continued proximity to each other, the realm was divided, re-organized and recast as the periphery of emerging centers of power. Nishapur now found itself along the edges of the Iranian nation and, by the logic of nationalism, more connected to the distant city of Tehran than the closer Afghan city of Herat. The gradual dismantlement of the great colonial power structures of the nineteenth century, allowed for the rise of third world nationalism throughout the twentieth century. Transforming nationalism into a post-colonial ideology required the nation, as a community and as an identity, to reformulate the past with the present in mind. Nishapur may have historically enjoyed a closer relationship to Herat than Tehran, but as a city in the modern Iranian Nation, Nishapur’s past had to be understood as being more intimately tied to Iran than any other nation. The accessibility and interconnection of the Central Asian cities that had allowed Khurasan to prosper as a locus of intellectual and artistic achievement was rendered impossible by the imposition of borders. As the old center fractured, new ones emerged—pulling Khurasan’s iconic figures and cultural history with them. Khurasan receded until it became no more than the borders that now divide it.

Nationalism not only fractured Khurasan’s geography, but dissected and co-opted its cultural legacy as well. A shared history needed to be manufactured and promoted as the basis for legitimacy. Ferdowsi, Rudaki, Biruni, Ibn Sina, Omar Khayyam, and many other figures’ historical authority and significance was without question and nationalists could seize each figure and co-opt them for their needs. If Khurasan could be forgotten, then each of them could be remade in the image of the nation.

The division of the land provided a territorial framework for dividing the historical figures among the states. Rudaki, for example, may have served the Samanid court in modern-day Uzbekistan, but had been born and died in modern-day Tajikistan and as a result, was claimed as an icon of uniquely Tajik identity and achievement. Rudaki and Ibn Sina, moreover, have been so explicitly deemed representatives of the Tajik state that both can be found on somoni banknotes. Ferdowsi, who also served in a court in Uzbekistan, was Iranian-born and became the cultural centerpiece of Reza Shah Pahlavi’s creation of an Iranian national identity. One of the first historical sites to be celebrated in Pahlavi Iran was Ferdowsi’s tomb (Ringer 267). Ferdowsi statues, streets, parks, and metro stations are strewn across Iran and while most street names in Tehran changed following the Revolution of 1979, Ferdowsi Avenue was of the few to remain. In Kazakhstan, Farabi has been so individually venerated by the state that his likeness appears on not one, but seven different tenge notes (the 1, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000, 5,000, and 10,000). Turkey, rather ironically, once used a 5000 lira note that featured a portrait of the secular nationalist Ataturk on the front with the figure of the Persian Sufi, Rumi, on the reverse. Biruni’s appearance on Syrian, Iranian, and Egyptian stamps signals how even somewhat unrelated states seek to associate themselves with the image of Khurasan’s writers. As these major theologians, poets, and scientists were elevated as icons, Khurasan was necessarily pushed to the margins of history.

As centuries passed, the remarkable achievements of Khurasan’s intellectuals eclipsed the community that allowed them and their ideas to flourish. The banknotes and boulevards that now represent those iconic scholars have, similarly, overshadowed the scholars themselves. The statues and the banknotes have become cardboard cut-outs of figures that, today, represent little more than the legitimacy of the state.

Previously a political, intellectual, and cultural center, Khurasan was forced to become an eternal periphery, only discernible through the borders that divide it and the nationalism that consumed its greatest figures. For the nations to usurp the political power the individuals’ legacies carry, the cultural and political power of Khurasan must be entirely forgotten. If Rudaki, Ferdowsi, and Farabi are all seen as representing the intellectual milieu of Khurasan, then they cease to be symbols of nationalism. Whereas, if Khurasan ceases to exist in cultural and historical memory then Rudaki can be Tajikistan’s possession, Ferdowsi may belong solely to Iran, and Kazakhstan can lay claim to Farabi. The emergence of a new power structure requires the irrelevance of the old. The establishment of new political and cultural centers, similarly, requires the appropriation of the former center’s accomplishments.

Samuel Tafreshi is an Iranian-American writer and activist raised in the U.S. and England. They hold a BA in Religion and their work has focused on comparative analysis of Persian and Western literature, while also exploring the presence of Islam in the activity of Muslims historically considered un-Islamic. Recently, they have been researching political protest throughout the South Caucasus states.